The legacy of this case must not rest in legal archives; it must be lived and realised in every accessible courtroom, every inclusive public space, and every law that treats all citizens with equal worth and dignity.

By

Dr. Tanwi Shams,

Assistant Professor of Law & Director Centre for disability Law and Advocacy,

National Law University Odisha.

E-mail: shams.tanwi@gmail.com

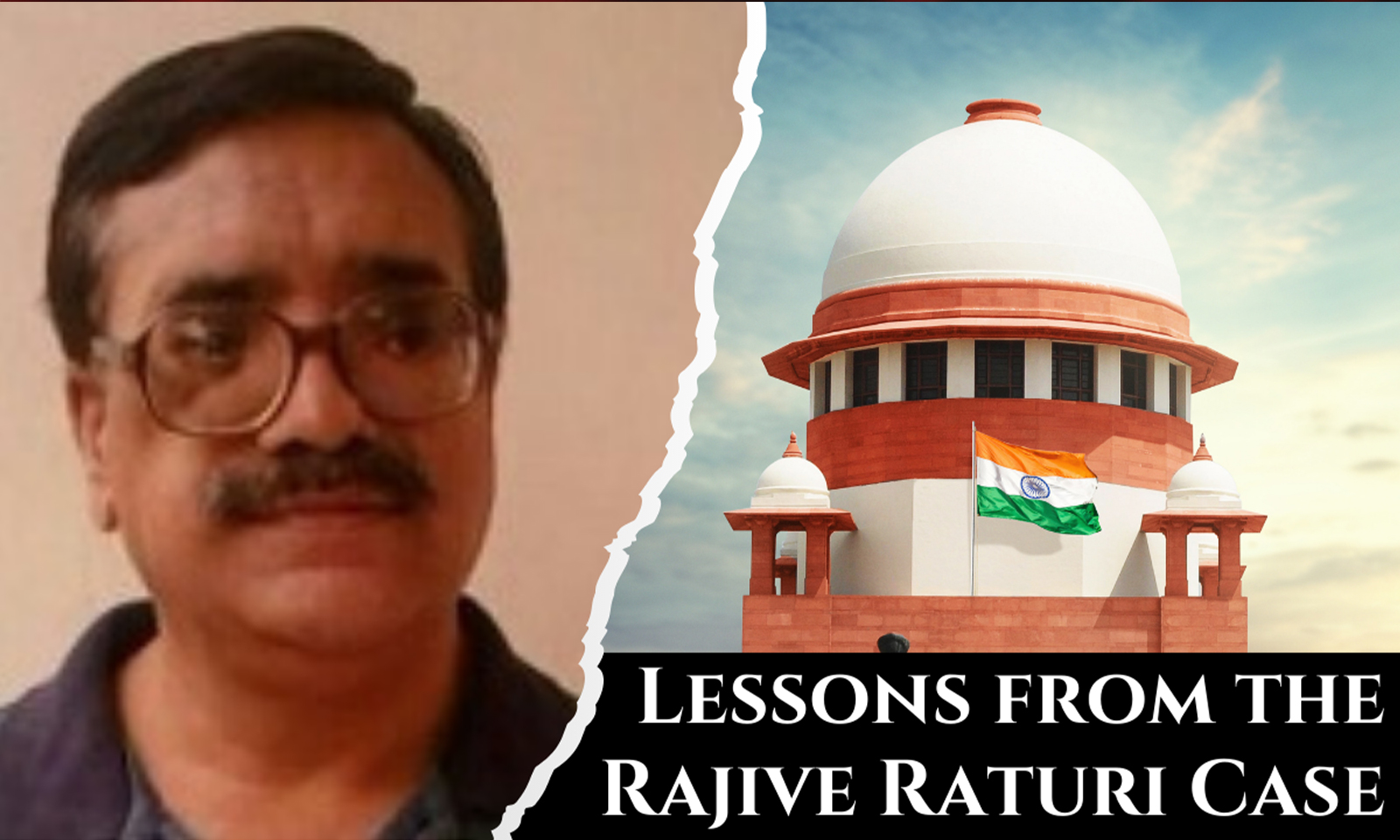

In the Indian jurisprudential landscape concerning the rights of persons with disabilities, the Supreme Court’s landmark verdict in Rajive Raturi v. Union of India stands as a transformative pronouncement. Rendered under the constitutional canopy of Article 14 (equality before the law), Article 19(1)(a) (freedom of expression), and Article 21 (right to life with dignity), the judgment articulated a compelling mandate for ensuring accessibility for persons with disabilities (PwDs) in the justice delivery system and other public institutions.

Post this judgment, a critical analysis is warranted to understand both its retrospective influence and the forward-looking obligations it imposes upon the State and society. The decision was hailed as a constitutional realisation of substantive equality which indicates a shift from a welfare-centric approach to a rights-based paradigm but to note its operationalisation remains marred by systemic inertia, infrastructural inadequacies, and institutional apathy.

Retrospective Juridical Significance

At its core, Rajive Raturi who is a public interest litigation invoking the constitutional rights of visually impaired persons and persons with reduced mobilities , seeking enforcement of accessible infrastructure and procedural accommodations in courts and tribunals across the country. The petitioner, himself a noted disability rights activist, argued that the inaccessibility of judicial fora and governmental institutions amounted to de facto exclusion from access to justice which is a fundamental right guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution of India.

The Supreme Court, in its wisdom, accepted the petitioner’s contention and issued a series of directives invoking the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016.The Court directed all High Courts to formulate accessibility guidelines for subordinate courts, conduct accessibility audits, and implement infrastructure that complies with the principle of universal design.

The Court underscored that mere formalistic adherence to legal provisions is insufficient. What is required is a substantive approach that ensures real and effective access. The doctrine of reasonable accommodation was affirmed as a legal necessity under Section 2(y) of the RPwD Act, 2016, aligning Indian law with Article 2 and Article 9 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), to which India is a signatory.

This was jurisprudentially significant because the Court expanded the scope of Article 21 to encompass access to legal institutions and public spaces as integral to the right to live with dignity. It re-affirmed that equality must be substantive rather than merely formal, and that any systemic barrier that disproportionately disadvantages PwDs is constitutionally impermissible.

The Implementation Deficit

Despite the normative and legal clarity established by the Raturi case, the actual ground-level implementation has been patchy at best. Accessibility continues to be viewed through a limited lens, often reduced just to installing ramps or elevators , whereas the judgment clearly mandated a more holistic and structural transformation, including signage in Braille, tactile flooring, accessible digital platforms, sign language interpretation, and court procedures compatible with assistive technologies.

Several High Courts have issued circulars or constituted committees, yet the actual compliance with the Supreme Court’s directions is neither uniform nor adequate till date. Annual accessibility audits, which were to serve as monitoring mechanisms, remain either incomplete or are treated as perfunctory exercises. Accessibility standards prescribed by the Harmonised Guidelines and Space Standards for Barrier-Free Built Environment for Persons with Disabilities and elderly persons as well have largely remained aspirational.

One of the fundamental challenges lies in the administrative mindset that views accessibility as a matter of logistical convenience rather than a non-derogable legal right. Budgetary allocations for accessibility are either meagre or subsumed under other heads without specific earmarking. Moreover, data pertaining to accessibility compliance is largely unavailable or non-transparent, which impedes public accountability.

Prospects and Legal Imperatives

The Rajive Raturi judgment must now be viewed not merely as a historical directive, but as a living constitutional mandate. The road ahead requires robust legal and institutional reforms:

1. Legally Enforceable Accessibility Codes: Accessibility standards must be made legally binding across all public and private infrastructure, with penalty clauses for non-compliance.

2. Mandatory Accessibility Audits and Reporting: High Courts and tribunals must submit annual compliance reports to the Department of Justice and the Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities, made public to ensure transparency.

3. Digital Accessibility Laws: With the proliferation of e-courts and virtual hearings, the need for universally designed digital infrastructure is urgent—compliant with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) and compatible with screen readers.

4. Institutional Sensitization and Capacity Building: Judicial academies, bar councils, and law universities must incorporate mandatory modules on disability rights and procedural accessibility.

5. Legal Aid and Support Systems: Legal services authorities must develop inclusive legal aid mechanisms to assist PwDs, ensuring that procedural justice is both meaningful and accessible.

6. Civil Society Monitoring: NGOs and other Social welfare based institutions must continue to engage in strategic litigation and monitoring to hold public authorities accountable.

Thus in conclusion this landmark case of Rajive Raturi v. Union of India symbolizes the judiciary’s recognition that accessibility is not a tokenistic gesture but a constitutional and statutory right integral to the full and equal participation of persons with disabilities. The verdict bridges the gap between law and lived reality, but that bridge remains incomplete without our further efforts.

It is incumbent upon the State, civil society, and institutions of governance to translate this landmark judgment into tangible outcomes. As India aspires to be a truly inclusive democracy, the test of that aspiration will lie in ensuring that no citizen is denied access to justice, dignity, or opportunity by virtue of disability.

The legacy of this case must not rest in legal archives; it must be lived and realised in every accessible courtroom, every inclusive public space, and every law that treats all citizens with equal worth and dignity.